For thousands of years, the breathtaking landscapes of British Columbia have been anything but untouched or wild—they have been shaped, cultivated, and carefully managed by Indigenous knowledge keepers. However, much of this deep-rooted history has been obscured by colonial narratives that falsely depicted the region as a vast, untamed wilderness. Now, groundbreaking genetic research has confirmed what First Nations communities have always known: their ancestors were not passive foragers but sophisticated agriculturalists, ecologists, and land stewards, actively cultivating and transplanting beaked hazelnuts (Corylus cornuta) across vast distances for sustenance, medicine, and trade.

By deciphering the genetic code of hazelnuts found throughout British Columbia, scientists have unveiled a 7,000-year legacy of Indigenous cultivation, selective propagation, and translocation. This scientific breakthrough fundamentally challenges settler-colonial myths and spotlights the advanced agricultural traditions of First Nations groups such as the Gitxsan, Tsimshian (Ts’msyen), and Nisga’a, whose expertise in plant management significantly shaped the ecological diversity and food systems of the region.

Ancient Hazelnut Cultivation: A 7,000-Year-Old Practice

Long before European contact, Indigenous communities in British Columbia relied on the beaked hazelnut not just as a food source, but as an essential component of their daily lives. Rich in protein and healthy fats, hazelnuts served as a sustaining staple in traditional diets, while their oils were pressed for medicinal salves and cosmetic applications. The plant’s durable, flexible wood was harvested for crafting tools and even used in the construction of snowshoes and baskets, demonstrating a deep understanding of ecological materials and their practical applications.

Oral histories, passed down through generations, describe Indigenous peoples intentionally cultivating hazelnut groves, using prescribed burns and selective pruning to encourage healthy growth. Unlike modern large-scale monoculture farming, Indigenous cultivation practices were in harmony with nature, supporting biodiversity and ensuring sustainability for future generations. The genetic evidence extracted from over 200 hazelnut specimens across the province corroborates these oral traditions. Scientists have identified five distinct genetic clusters, proving that Indigenous peoples were deliberately moving and propagating hazelnuts over distances of up to 800 kilometers—a pattern that cannot be explained by natural seed dispersal through birds or squirrels alone. This demonstrates that active land stewardship and sophisticated plant management were taking place long before Western agricultural systems arrived on the continent.

By tracing the genetic diversity of hazelnuts, researchers have pinpointed specific regions where cultivation was most prevalent, particularly near ancient settlements such as:

- Temlaxam, an advanced First Nations city that once thrived at the confluence of the Skeena and Bulkley rivers

- Kitselas Canyon, a historically significant Tsimshian village east of present-day Terrace

- Gitwinksihlkw, a central hub of the Nass Valley with deep cultural and agricultural history

- Hazelton, a modern town whose very name reflects its historical abundance of hazelnuts

The Lost City of Temlaxam: An Agricultural Hub

Among the most compelling revelations of this research is its direct link to the lost city of Temlaxam, a civilization known through the Adaawx (oral histories) of First Nations communities in northwestern British Columbia. Oral accounts depict Temlaxam as an expansive metropolis stretching over 80 kilometers along the Skeena River, bustling with commerce, trade, and intentional food cultivation. Modern genetic findings now confirm that hazelnuts were brought to Temlaxam from multiple regions and actively managed by its inhabitants as early as 7,000 years ago.

This suggests that First Nations communities in what is now British Columbia were engaging in large-scale food production at the same time ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt were cultivating wheat—a discovery that reshapes historical perspectives on agriculture in North America. Temlaxam’s decline, likely due to geological upheaval and natural disasters around 3,500 years ago, led to the dispersal of its people, who later became the ancestors of the Gitxsan, Tsimshian, and Nisga’a Nations. Yet, the genetic signature of their agricultural expertise remains encoded in the very trees that still stand in these regions today, a living testament to their deep relationship with the land.

Trade Networks and Linguistic Connections

The widespread distribution of hazelnuts across British Columbia was not simply an ecological phenomenon but a reflection of extensive Indigenous trade networks. The movement of hazelnuts aligns with ancient trading routes, which facilitated the exchange of food, goods, and agricultural knowledge between diverse First Nations communities. Perhaps even more fascinating is the linguistic evidence that mirrors this botanical exchange. The Gitxsan and Nisga’a words for hazelnut bear striking similarities to the Coast Salish terms, indicating that these communities adopted not just the nut, but also its name, through trade and cultural interaction. This linguistic connection serves as another irrefutable piece of evidence that hazelnuts were a commodity of significant value, deeply embedded in the social and economic framework of precolonial Indigenous life.

Colonial Erasure and the Fight for Land Rights

Despite thousands of years of sophisticated land stewardship, colonial settlers systematically erased Indigenous agricultural knowledge from historical records. For centuries, the dominant narrative suggested that First Nations people were merely foragers who passively took what the land provided, a misconception that justified the dispossession of their lands under the pretense that they were “unused” or “unoccupied.” Even today, Canadian courts require Indigenous nations to prove a continuous relationship with the land in order to establish Aboriginal title.

The landmark Tŝilhqot’in Supreme Court ruling of 2014 acknowledged that Indigenous land use extends beyond permanent settlements, yet legal battles for land rights remain steeply weighted against First Nations. The genetic evidence from hazelnuts offers powerful new support for Indigenous land claims, providing scientific validation of continuous, intentional land use stretching back millennia. This research fundamentally challenges Western definitions of agriculture, which have historically focused on annual crops like wheat and barley while disregarding Indigenous systems of perennial cultivation and ecosystem engineering.

As Jesse Stoeppler, Deputy Chief of the Hagwilget First Nation, succinctly puts it: “This proves that as Indigenous people, we have been thriving on this land long enough to share the wealth with others.”

Reclaiming Indigenous Knowledge for the Future

The rediscovery of ancient hazelnut cultivation is not merely a scientific breakthrough—it is a call to action. Many Indigenous leaders and food sovereignty advocates see this research as an opportunity to revitalize traditional food systems, reconnect with ancestral knowledge, and restore sustainable agricultural practices that have been suppressed for centuries.

Jacob Beaton, a Tsimshian leader and Indigenous food advocate, believes this is only the beginning: “Hazelnuts are just one of many. Now it’s time to look at other species—saskatoon berries, juniper, strawberries, raspberries. Indigenous horticulture and ecosystem management have been happening for a very, very long time.”

By reintegrating traditional land stewardship methods, First Nations communities can revive native plant diversity, enhance food security, and reinforce cultural resilience.

Beyond Beaked Hazelnuts: A Closer Look at Hazelnut Species

While the beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) has played a central role in Indigenous food systems for thousands of years, it is part of a much broader hazelnut lineage. Across North America, another native species, the American hazelnut (Corylus americana), thrives in the eastern woodlands, where it has been traditionally harvested by Indigenous nations for food, medicine, and trade. Though closely related to the beaked hazelnut, the American variety tends to produce larger nuts and is more commonly found in areas stretching from the Great Lakes to the Appalachian foothills.

Further afield, the European hazelnut (Corylus avellana)—the species behind the global hazelnut industry—has been widely cultivated for centuries. Introduced to British Columbia through commercial agriculture, European hazelnuts differ from Indigenous varieties in both genetics and farming techniques. Unlike the beaked hazelnut, which thrives in wild forests and managed groves, European hazelnuts are typically grown in large-scale orchard settings. However, as interest in regenerative agriculture and Indigenous food sovereignty grows, farmers and researchers are beginning to explore the potential of native hazelnuts as a more sustainable and resilient alternative.

Hazelnuts in the Present: Challenges and Revivals in British Columbia

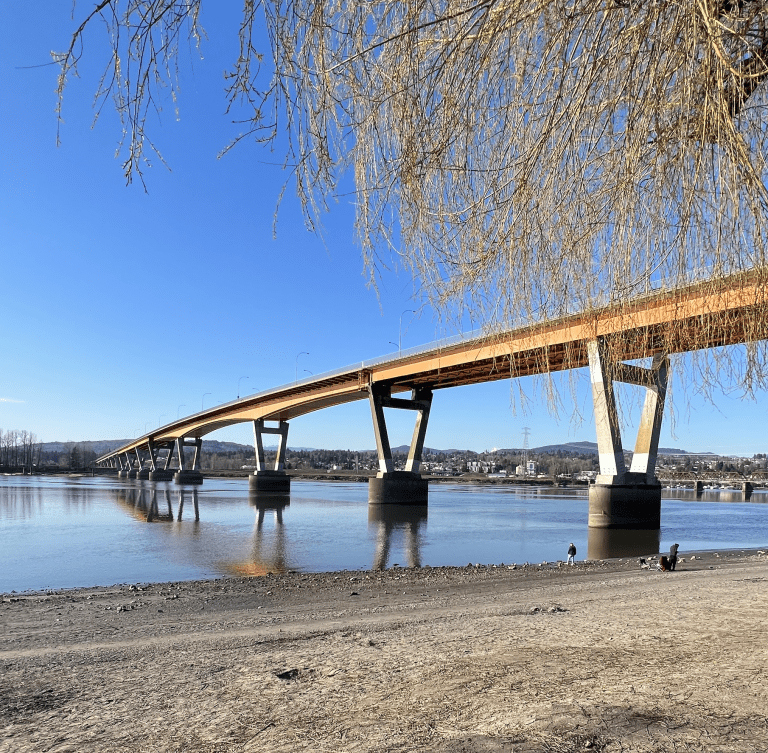

While Indigenous communities cultivated hazelnuts with remarkable success for millennia, today’s hazelnut industry in British Columbia faces a very different reality. In the late 20th century, the province saw a surge in commercial hazelnut farming, but by the early 2000s, an outbreak of Eastern Filbert Blight (EFB)—a devastating fungal disease—wiped out much of the industry. Many hazelnut orchards in the Fraser Valley were abandoned, and large-scale production nearly collapsed.

However, a new movement is emerging—one that blends modern agricultural science with Indigenous knowledge. Some farmers are reviving hazelnut cultivation using disease-resistant hybrids, while others are turning to native hazelnuts, which have thrived in the region for thousands of years without human intervention. Additionally, Indigenous food sovereignty advocates are reclaiming traditional land stewardship practices, reintroducing native hazelnut groves, and exploring the economic and ecological benefits of these ancient trees.

As British Columbia looks to the future of hazelnut farming, there is growing recognition that sustainability lies not in imported monocultures, but in the wisdom of the past—where Indigenous communities nurtured diverse, resilient food systems in harmony with the land.

A Legacy of Cultivation and Stewardship

The story of hazelnut cultivation in British Columbia is far more than a historical footnote—it is a testament to the enduring ingenuity, ecological wisdom, and agricultural mastery of First Nations peoples. For 7,000 years, Indigenous communities have shaped, nurtured, and expanded the range of beaked hazelnuts—a living legacy that persists in the forests, valleys, and food systems of British Columbia today.

We at Wild Bluebell Homestead are honored to share this remarkable history with you. Thank you for taking the time to read our blog! We would love to hear your thoughts—what Indigenous agricultural knowledge or sustainable farming techniques should we explore next? Drop a comment below and let us know what you’d like to see featured around our homestead in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia! 🌿✨

Article Citations

Simon Fraser University

BC Food History

BC Hazelnut Growers

Technology Networks

PNAS Research Article

Archaeology Magazine

CBC News

Science.org

Tula Foundation

The Tyee

Phys.org